Home »

Jazz Articles » Book Review » No, Don Porfirio Did Not Invent Jazz, but It Doesn’t Matter

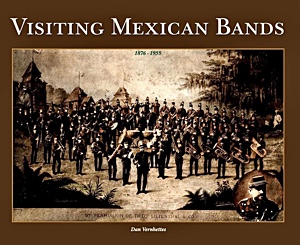

Visiting Mexican Bands, 1876-1955

Visiting Mexican Bands, 1876-1955

Dan Vernhettes

220 pages

ISBN: #9782900946046

2022

It is a safe bet that asking a group of music aficionados “Who invented jazz” is likely to elicit a range of answers from “Everyone” to “No One.” Even the earnest seeker is apt to come up with a

Louis Armstrong

trumpet and vocals

1901 – 1971

” data-original-title title>Louis Armstrong-like formulation of “lots of ingredients,” which is certainly true. But we live in an age in which the phrase “cultural appropriation” is sometimes heard, suggesting that, at least, someone is making a living off of someone else’s creation. It is not a complimentary evaluation, even if sometimes true.

So it is occasionally a relief to have someone who is willing to get his or her hands proverbially dirty and do the thankless research needed to establish a claim of priority, or originality, or ownership, or influence. Dan Vernhettes is one such person, a cornet player turned scholar, who has produced a most interesting book, Visiting Mexican Bands, 1876-1955 which, if nothing else, can lay to rest a few contemporary myths about the origins of the music. It is not, one must emphasize, that Vernhettes says Mexico had nothing to do with early jazz. That is assuredly not what he says. What Vernhettes does do is describe, indeed, almost concert by concert, the role of Mexican military bands in bringing new instruments, rhythms, harmonies, repertoire and probably techniques to audiences and musicians starting during the presidency of Porfirio Díaz (1876-1910) in Mexico. While the bulk of the original research was done in newspapers, Vernhettes has clearly had access to acres of sheet music, programs, photos, recordings and more as primary source material. The result is a marvelously illustrated and handsomely produced volume that most assuredly does not claim that Porifirio Díaz invented jazz, but that musicians in his employ (at least sometimes) contributed substantially to it. And Vernhettes shows how. This is, of course, a subtle and complex story in which a reader is invited to connect the dots in search of a narrative, perhaps several, all equally plausible, but each with a kind of different angle. Very few will ever read this volume from cover to cover, but anyone interested in the Latin influence on jazz from a rather different angle than the familiar Cuban one will benefit by looking at it . Influence is where you find it, but best be sure the influencers were actually around and doing what you think they did when they did it.

Ironically, the story really begins, not in Mexico, but in Belgium with Adolphe Sax (1814-1894), progenitor of the saxhorn and the saxophone in the 1840s. The French military presence in Mexico (1862-1867) may have well brought the saxophone there. In 1884, at the urging of an executive of the Mexican National Railway, the Mexican government sent the Eighth Cavalry Band to the New Orleans World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition (1884-1885), where the country had several exhibition halls, one to house the officers and men of the Mexican army. The reason for their presence as musical ambassadors was that Mexico, under Díaz. was bent on modernization and attracting foreign capital and technology to promote economic growth. And these musicians, all spit and polish and highly trained, were intended to burnish Mexico’s image, which had suffered badly from political turmoil, invasion and civil war in the nineteenth century. It was prospective investor public relations, the nineteenth-century equivalent of a dog and pony show. It worked.

The Eighth not only played extensively in New Orleans but travelled to Chicago, Columbus, Cleveland, Buffalo, Boston, Pittsburgh, Memphis and New York by rail under the leadership of Captain Encarnacion Payén. a well-regarded cornet player (who once escaped execution in Mexico by playing!). The band, nearly 70 members in all, played an extensive selection of light classics, to much favorable press much of which is minutely documented, When the Eighth returned to Mexico, a couple of its members stayed behind in New Orleans, including soprano saxophonist Leonardo Vizcarra and clarinetist Florencio Ramos, “the first saxophone wizards in New Orleans who served as models for Creole musicians” both through the playing and teaching. This is not simply some wild guess. Vernhettes has done his homework and gone into the manuscript Federal censuses to find locate them. So one knows where they were, what they were doing, and when.

What he has not done is succumb to some dubious speculations about how Porfirio Díaz invented jazz, or how black musicians in New Orleans imitated Mexican players, with even the term “jazz” derived from “jarabe” ( a popular dance in Mexico in duple meter). His claims are modest, but substantial and substantiated. Moreover, as he points out, once the Eighth had left for home, there was an almost continuous stream of Mexican bands and musicians touring, in the United States in its wake, including one that played at Coney Island, New York in June 1886.

What Vernhettes also does not shy away from is correcting the burgeoning myth that some Mexican players, such as the Tio-Hazeur family, virtually conjured up the clarinet in New Orleans. In point of fact, the Tios were not Mexicans, but what Vernhettes calls Spanish/French/African Creoles. “The short time that the Tios spent in Mexico cannot be considered decisive for their supposed Mexican influence on New Orleans music.” Another musician from Mexico, Carlos Curti, who was actually Carmine Curti, born in Potenza, Italy, toured with the Mexican Typical Orchestra, was a xylophonist, travelled extensively in the United States, and ultimately ended up directing an orchestra at the Waldorf Astoria in Manhattan. Vernhettes devotes considerably more attention to him (and his brothers) in preference to the Tios because the Curtis were more influential. And if a reader is curious about who in the United States influenced Mexican playing in its earlier days, Vernhettes points to

Paul Whiteman

composer / conductor

1890 – 1967

, who intrigued Jose Briseño and the National Conservatory of Mexico in the 1920s.

There is much more to see in this fascinating volume, probably as much for students of music in Mexico as elsewhere. What is clear is that New Orleans, as cosmopolitan a city as one could find, was a gateway to products, people and Caribbean and “Latin” influences of the most diverse sort. It was to Mexico then what Houston is today: a gateway. Vernhettes’ work will be a required reference for historians of early jazz and Mexico’s undoubted contribution to it.